Political Musings of Thursday December 11, 2025

By Ike Abonyi

"I still believe that the one thing that will bring peace, absolute peace, to this country—the type of peace we want attached to development—is to liberate Ndi Igbo, and there is no better act of liberation than accepting that they have equal rights in Nigeria." - Emeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu.

In this political dispensation, the geographical North has historically posed challenges to realising an Igbo Presidency. This is an empirical fact, but the upcoming opportunity in 2027 presents a valuable chance to overcome these obstacles. Given the steadfast support that Ndigbo have consistently demonstrated, this moment calls for thoughtful reflection and proactive action. All stakeholders must unite in their efforts to foster a more inclusive and representative future for everyone.

It's not uncommon to hear narratives suggesting that Igbos are failing to navigate their political landscape effectively. This portrayal is not factual, even though some within our own community are even starting to internalise this perspective. However, for those of us who have closely followed the political evolution of Ndigbo from the Second Republic to the present, that viewpoint is pure blackmail, as there are substantial reasons to examine the role of the geopolitical North in shaping these dynamics, particularly in relation to the quest for an Igbo president. History is a witness that all failed Igbo Presidency projects since 1999 have a Northern imprint on them.

Looking back, we see clear evidence of these political currents. For instance, just nine years after the civil war, in 1979, Alhaji Shehu Shagari innocuously selected Dr Alex Ekwueme as his running mate. This decision surprised many due to Ekwueme's relatively low political profile at the time compared to other prominent figures on the stage, such as K.O. Mbadiwe and C.C. Onoh. However, Shagari's choice proved to be vital, as Ekwueme became an impactful force within that administration from 1979 to 1983, highlighting a strong partnership that many viewed as a promising path for future political leadership.

Tragically, the political momentum toward a peaceful transition in leadership was abruptly halted by a coup, orchestrated by some Northern figures who ostensibly sought to prevent an Igbo leader from ascending to the presidency. The subsequent years saw a recurring pattern, with key Northern leaders, such as Muhammadu Buhari, Abdulsalami Abubakar, and Ibrahim Babangida, playing significant roles in these manoeuvres, often at the expense of potential Igbo leadership.

Fast forward to the return to democratic governance in 1999, when the country faced the critical decision of which candidate would lead Nigeria. It was during this time that Alex Ekwueme, a staunch advocate for democracy, found himself again overshadowed by Northern power brokers who favoured Olusegun Obasanjo. Ekwueme had been pivotal in organising the political framework that shaped the transition back to democracy. During the 1998 PDP national convention in Jos, his candidacy was widely seen as a natural choice to represent the interests of the southern regions, specifically the Igbos and the Yorubas.

However, in a surprising turn of events the night before the voting, some influential military figures from the North shifted their support to Obasanjo, ultimately sidelining Ekwueme once more. This highlights a significant challenge that has persisted in Nigeria’s political landscape: the need for genuine inclusivity and equal representation for all regions.

After Obasanjo’s tenure concluded in 2007, there was an expectation that power would return to the North, and he endorsed then-Governor Umaru Yar'Adua of Katsina State as his successor. The choice for his running mate generated significant interest, particularly with prospects of selecting someone from the Igbo ethnic group, such as Governors Peter Odili of Rivers State and Sam Egwu of Ebonyi State who were top contenders. However, similar to the decision-making process in 1999, key northern figures from Obasanjo's administration, including Nuhu Ribadu, then-Chairman of the EFCC, and Nasir El-Rufai, influenced the decision against anointing an Igbo but instead went for then-BAYELSA Governor Dr Goodluck Jonathan for the vice-presidential role—a choice that came unexpectedly to him, especially after he had just emerged the state Governor after the removal of his mentor and predecessor, Diepreye Alamieyeseigha.

Following Yar'Adua's death, Jonathan providentially ascended to the presidency. His leadership style often resonated with the Igbo population, who supported him massively. Still, it caused a reaction from the North, leading to a unified effort to replace him over zoning, ultimately resulting in the rise of the opposition party, with the late General Muhammadu Buhari as their candidate.

With Buhari's presidency concluding in 2023 and power shifting back to the South, there was speculation that the presidency could finally be awarded to the Ndigbo, the only significant ethnic group in the South that had not yet held a leading role. Figures such as the late Ogbonnaya Onu, Emeka Nwajuba, and Rotimi Amaechi in Buhari’s ruling APC were considered potential candidates. However, the North curiously again favoured another Northerner, then Senate President Ahmad Lawan. This choice sparked discussions about unity, as certain ambitious Northerners, led by El Rufai, feeling sidelined by Buhari’s indecision, which harmed their running mate ambition, decided to align themselves with Bola Ahmed Tinubu instead.

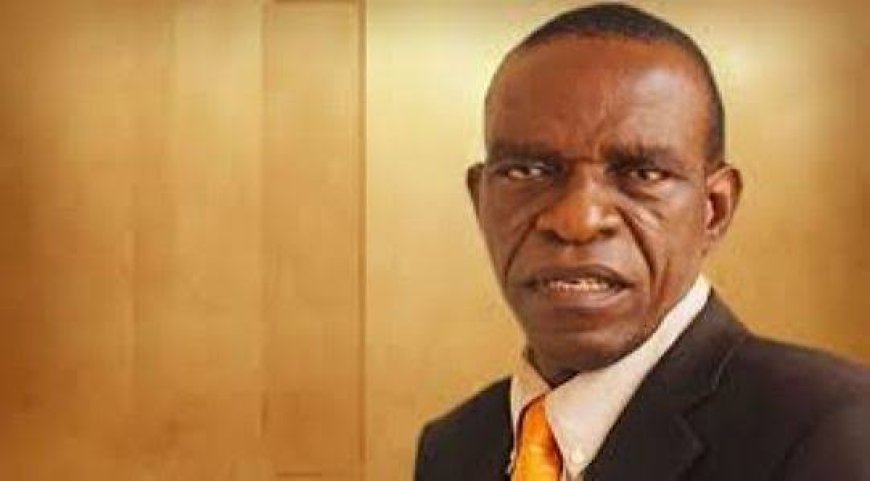

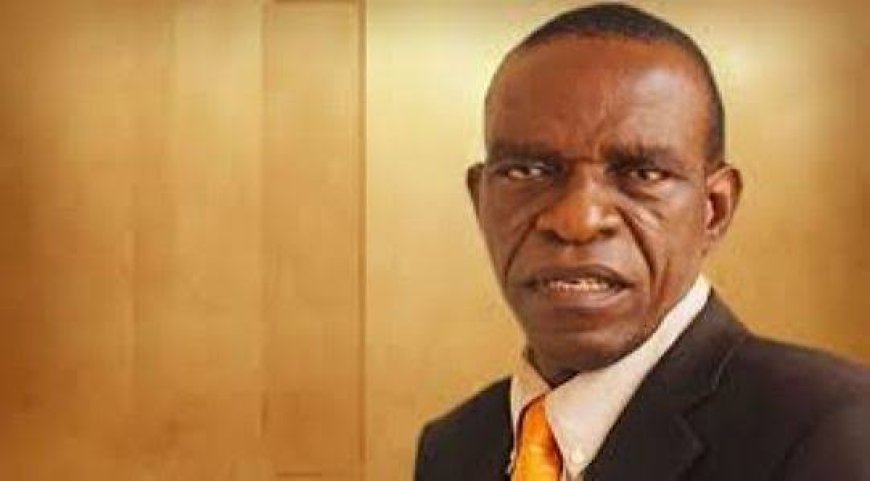

It is therefore crucial to rethink the narrative around why it seems the Igbos have not secured the presidency, particularly by examining the political dynamics of figures like Obasanjo, Jonathan, and Tinubu compared to Alex Ekwueme and Peter Obi. Which effort did Obasanjo, Jonathan, and Tinubu put into getting the President more than what Ekwueme and Peter Obi did? In other words, getting the Presidency in Nigeria is about getting Northern favour not about working hard. The only Southerner since 1999 who really worked hard manoeuvring the North is Tinubu; others, Obasanjo and Jonathan, literally did nothing. Dr EKwueme and Peter Obi combined have worked harder than any Southerner to be President but did not get it.

Even in the opposition party, despite the significant support Ndigbo provided the PDP over many years, their consistent loyalty did not culminate in an endorsement for an Igbo candidate. Peter Obi's emergence as a serious contender for the party’s ticket in 2023 was ultimately overshadowed by the selection of a Northerner even against zoning considerations. An action that forced him out of the party.

Historically, as is evident, there have been barriers faced by the Igbos during various elections with the North playing significant roles.

Looking forward to 2027, therefore, there is an expectation that collaboration can be fostered offering a chance to reflect on the importance of inclusivity in the political sphere.

It's essential to understand this historical context to foster constructive dialogue as we approach future elections. Engaging in meaningful discussions can empower those involved to confront these longstanding dynamics. Moreover, the legacy of the civil war, which ended over 55 years ago under the ‘no victor, no vanquished’ understanding, provides an opportunity for healing and reintegration to take centre stage. No better way to pronounce the war finally ended than seeing an Igbo occupy Aso Rock.

The Nigerian political landscape is intricately shaped by diverse regional interactions, with the Igbos often finding themselves at a disadvantage. For genuine progress, all parties need to recognise the constructive dialogues the Ndigbo have been pursuing.

It is important to recognise that the challenges faced by the Igbo people in pursuing the presidency in Nigeria are not solely due to the unique political dynamics of the region. Instead, they are influenced by the broader mindset of various partners within the framework of WAZOBIA, where some may inadvertently overlook the aspirations of others.

To foster a better political landscape, all stakeholders in Nigerian politics must confront and address these historical challenges. By promoting unity and establishing open platforms for meaningful dialogue, we can work towards a more equitable political environment. This approach will enable every ethnic group, including the Igbos, to aspire to and successfully attain the highest offices in the country. Together, we can strive for a more inclusive Nigeria that acknowledges and values the contributions of all its citizens.

If a coalition like the African Democratic Congress, ADC, for instance, hopes to be impactful in their desire to kick President Tinubu and APC out of Aso Rock, the geographical North within it must seize this beautiful opportunity of Ndigbo being favoured by zoning and having the indisputable best candidate in the market in Peter Gregory Obi. Not to do that is to continue to fuel injustice and keep the trajectory that has now brought us close to the dyke as a country. A new Nigeria is not only possible but desirable. Let 2027 be the turning point. God help us.