Insecurity: Nigeria in an Age of ‘Juju Theology’

In moments such as these, when Nigeria’s public sphere quivers under the weight of grief, confusion, and collective anxiety, one must begin with sobriety.

By Prof Chris Agbedo

In moments such as these, when Nigeria’s public sphere quivers under the weight of grief, confusion, and collective anxiety, one must begin with sobriety. The grim headlines that populate our national discourse today are not abstract tragedies; they are daily experiences of everyday Nigerian shaping the consciousness of communities, churches, and homes. And so, as we gather our thoughts to examine a troubling pastoral utterance – an instruction to Christians to “go and do juju” for personal protection – we must acknowledge the broader climate in which such theological distortions germinate. This is not a matter of sensationalism. It is a matter of national soul-searching. For when spiritual leaders, custodians of moral imagination, begin to recommend syncretic survival kits as part of a Christian’s protective arsenal, it signals not merely doctrinal drift; it reveals a deeper societal existential challenges. Our reflections, therefore, must be laced with empathy, couched in historical consciousness, illuminated by Scripture, and sharpened by civic responsibility.

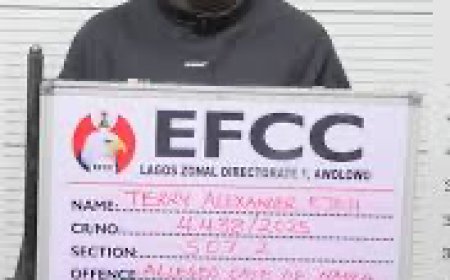

A ‘Pastor,’ Oloruntimilehin Daramola had, in a viral TikTok video, urged his congregation to ‘get fortified’ as protection against attacks by terrorists. When a Nigerian pastor tells his congregation to “go and do juju” so that guns will “face themselves” if bandits attack, he is not merely preaching heterodoxy; he is announcing the collapse of faith under the crushing weight of fear. In any normal society, such a message would be dismissed as bizarre, reckless, or even comical. But Nigeria is no longer a normal society. In this distressed climate, his message lands as not only scandalous and heretic but strangely symptomatic of a desperate improvisation in a country where insecurity has become a sovereign entity.

The pastor’s argument – “I can’t be fortified alone while my members remain exposed” – echoes the cry of a shepherd overwhelmed by wolves. Yet, it also echoes some of Scripture’s darkest chapters, moments when fear became doctrine, and doctrine became a tool for panic instead of hope. Like the elders of Israel in 1 Samuel 4, who fetched the Ark of the Covenant as a charm because the Philistines were too terrifying, this pastor invokes God but turns to alternative fortification. Like Saul at En-dor, he does not deny God; he simply fears that God alone is no longer enough. And like Jeroboam, who built unauthorized shrines to secure political advantage amid perceived threats, this pastor constructs a new ‘juju theology’ out of insecurity.

Yet the question that must now be asked with brutal honesty is this: Who really pushed this pastor to the brink of syncretism? Before we stone the shepherd, let us examine the landscape in which he grazes. The constitutional mandate of any responsible government is unambiguous –

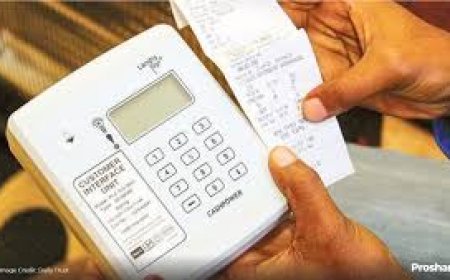

to secure lives and property, and promote the welfare of citizens. But what has the Nigerian government – past and present – done with this sacred trust? Today, insecurity is not merely a problem. It is an epidemic; it is a metastasis. It has become a shadow that darkens everything from agriculture to education, worship to travel. Security breaches are no longer occasional; they are the norm. National shock has become a weekly ritual. An army general is ambushed and killed. School children are abducted in sweeping numbers. Some are said to have “escaped.” Some are said to have been “rescued.” Some are “recovered” – a kind of linguistic circus or discursive warfare that depends entirely on who is speaking.

Yet, nothing is said – or known – about the abductors. Were they arrested? Interrogated? Prosecuted? Deterred? Deafening silence! Shrugging. Evasion. In one of the most interesting remarks in recent memory, the Police boss reportedly declared that the kidnappers of Kwara church worshippers were not arrested because they voluntarily opted for a peace deal. Opted? Peace deal? With terrorists? A sovereign state casually outsourcing security management to abductors? What ransom was paid? One billion naira? Some allege yes. Others scoff and deny. And the ding-dong continues while Nigerians bleed. If this is not an apocalyptic sign of a failing state, what then is it?

Then came the Kebbi school abduction – one of the most mystifying episodes in our insecurity chronicle. Twenty-four innocent students were taken in a sweeping operation that should have been impossible under proper security watch. It equally came with the most disturbing detail -security personnel had reportedly been withdrawn from the Maga School shortly before the kidnappers struck. Withdrawn by whom? The Kebbi State Governor does not know.

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu asked questions. He is yet is volunteer an answer to Nigerians. Two chief executives – state and federal – both maintaining sealed lips over an ‘order affecting citizens’ lives. Is this mere disorganization? Or is this complicity? Sabotage? A coordinated dereliction? A system eaten from within? Nigeria has reached a point where insecurity has become mystery mystified, an elaborate puzzle, whose pieces are deliberately scattered or simply wrapped in mystery.

And in this fog of uncertainty, fear is no longer an emotion; it is now a national operating system. When the state charged with ensuring safety cannot account for security directives…

When abductors negotiate freely…

When ransom becomes an unofficial tax…

When generals die like civilians…

When children disappear like statistics…

When churches, mosques, markets, and schools become soft targets…

Who truly blames a pastor, however theologically misguided and outlandish, for seeking alternative fortification?

Wrong as he is, he is but a symptom of a deeper affliction; a sovereign state, whose citizens feel abandoned by a government that appears more reactive than proactive, more rhetorical than resolute, more puzzled than prepared. It is in such climates that doctrines mutate, faith buckles, and syncretism dresses up as pragmatism. But we must also insist on clarity. It is true that ‘ anụ gbaa ajọ ọsọ, a gbaa ya ajọ egbe’ (a game’s dangerous escape bid elicits dangerous shooting). However, desperation does not excuse doctrinal distortion. Fear cannot be baptized as theology.

Panic cannot become pulpit teaching. Biblical faith has always been tested in times of national crises – from the siege of Jerusalem to the persecution of the early church. Yet, Scripture consistently warns against resorting to spiritual shortcuts, no matter how frightening the circumstances. The problem is that Nigeria’s insecurity has stretched religious communities to breaking point. The pastor’s sermon is a signal of how deeply national trauma is eroding theological boundaries. But it is equally a signal the extent to which the government has failed in making citizens feel protected.

Shortly before he ‘resigned on health ground,’ the former Defence Minister, Mohammed Badaru was widely quoted as claiming that bandits are located in forests, which bombs can’t penetrate! “Yes, we know their locations, but some of these areas are places, where direct strikes could endanger civilians, or forests where our bombs cannot penetrate…” What kind bomb be that? Imagine! Can you beat that? Well, Pastor Daramola is panicking because the Nigerian state has bombs that can’t penetrate forests. The pulpit is trembling because ‘not all bandits are criminals’. Syncretism is rising because the ‘bandits are our brothers’. This is the ecology of fear in which bizarre teachings flourish. Truly, ‘Naija na cruise’!

Well, the message is painfully clear. When citizens begin to forage for metaphysical self-defence, they are no longer merely afraid; they are hopeless, hapless. Nerve-jangling fear has become one huge pressure-cooker eating up and gnawing away every drop of human essence in us all. And when hopelessness meets insecurity, the social contract collapses. The government must understand that the pastor’s syncretic counsel is not a theological problem alone; it is a national emergency signal. It is society screaming: “We do not trust you to protect us.” The indictment is clear and unmistakable. And it is coming not from activists, not from the opposition, not from political analysts, but from the pulpit. The sovereign state stands at a dangerous intersection –

a state struggling to secure itself; citizens improvising survival strategies; faith communities bending under fear and advocating ridiculous security strategy; doctrines mutating under stress.

This is what insecurity has done to Pastor Daramola’s brand of Christianity in Nigeria. But it is also what insecurity has done – and is doing – to governance, social contract, trust, social cohesion, and national sanity. The pastor’s ludicrous sermon is a warning, a symptom, a metaphor for a broken system. If the government does not take this message seriously, the next stage is worse – a society where every individual becomes their own government, their own security force, their own protector, their own metaphysical warrior. At that point, governance itself becomes irrelevant. Before that abyss opens fully like a volcanic eruption, disgorging its molten lavas, those in power must act – decisively, transparently, courageously – to restore trust, rebuild security, and reaffirm the foundational principle of statehood, that is, a sovereign state, where citizens can sleep without bargaining for survival. President Tinubu’s recent moves, especially the appointment of General Chris Musa as Defence Minister, provide the basis for one to scoff at the compelling urge to end on a note of pessimism. The appointment has been widely heralded as a step in the right direction and should be sustained. Nonetheless, until this smart move of Mr. President begins to yield the much expected desired results, ‘juju theology’ will continue to flourish in the cracks of a frightened sovereign state. And the frightened citizens will continue to ask, in lament: Who, really, can blame the pastor?

...Chris Agbedo, Ph.D, a Professor of Linguistics University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Fellow, Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study, Amsterdam, is a public affairs analyst.

What's Your Reaction?