By Chris Agbedo

There is a bitter irony in the name of Ruth Maclean, the New York Times correspondent, who authored the January 18, 2026 report from Onitsha. Maclean suggests cleansing, moral hygiene, the careful washing of facts until they sparkle with credibility. Yet the assignment she undertook bears closer resemblance to the work of an undertaker than that of a cleaner: not the patient laundering of truth, but the cosmetic preparation of a narrative corpse, arranged neatly for Western consumption.

For what her report ultimately delivered was not illumination, but embalming—a carefully staged burial of complexity, with Emeka Umeagbalasi laid out as the principal cadaver.

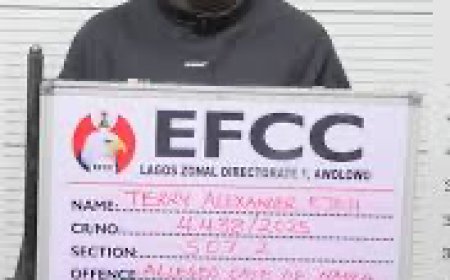

In the article, the reader first meets him not as an activist or researcher, but as a physical curiosity: a “short man,” one earbud dangling, weaving through sugarcane and wheelbarrows to a tiny stall of screwdrivers and wrenches. Before his ideas are interrogated, his poverty is catalogued. Before his claims are tested, his market stall is measured. The insinuation is subtle but unmistakable: how could truth possibly emerge from such a place?

From that moment, the report marches steadily toward its burial site. Umeagbalasi is accused, in effect, of having midwifed a global delusion: that Christians are being systematically slaughtered in Nigeria, a narrative supposedly powerful enough to animate U.S. Republican lawmakers and even to travel alongside American airstrikes. His data are dismissed as unverifiable, his methods casual, his sources “secondary,” his assumptions crude. He is allowed to speak, but only so that his words may indict him. He is profiled, but as a warning label, not as a participant in a violent and data-starved national tragedy.

Thus, the screwdriver seller becomes the screwdriver in the story—the small tool with which a vast diplomatic machine is supposedly dismantled. Here the journalism turns unclean. Because while Mr. Umeagbalasi was being symbolically buried in the pages of The New York Times, reality was busy refusing to cooperate with the narrative.

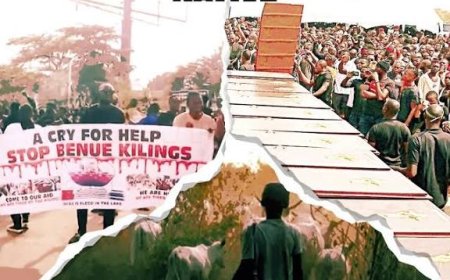

On January 20, 2026—barely forty-eight hours after Maclean’s literary inquest—USAfricaonline carried a report with a blunt headline: “Gunmen kidnap 163 worshippers from two churches in Nigeria.” The story quoted Reverend Joseph Hayab, head of the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) in the North, who said that elders of the churches told him 172 worshippers were abducted and only nine escaped. He described how attackers arrived in large numbers, blocked the entrances of the churches, and forced worshippers into the surrounding bush. No Google search was cited. No screwdriver shop was mentioned. No earbud was dangling from his ear. Yet the facts were no less grim.

One is tempted, then, to ask: where was Ruth Maclean? Where was The New York Times? Was Reverend Joseph Hayab also interviewed beside a wheelbarrow of sugarcane? Does he, too, sell spanners and pliers between church services? Should his cassock be searched for a hidden toolbox before his testimony is admitted into the court of Western credibility? Or is credibility, like baptismal water, selectively sprinkled?

In Maclean’s universe, the problem is not that Nigerians are being kidnapped in their churches; the problem is that a Nigerian dared to count them badly. The American empire, in this telling, does not act from ideology, from domestic culture wars, from evangelical lobbying networks, from strategic calculations, or from the gravitational pull of the arms industry. No. It acts because a man in Onitsha owns a shop that sells screwdrivers.

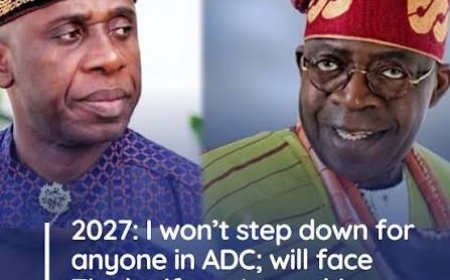

This is not political analysis; it is folklore. Power does not flow upward from market stalls to the White House. It flows downward—from senators seeking re-election, from churches seeking converts, from contractors seeking wars, from think tanks seeking relevance, from lobbyists seeking their next invoice. And here lies another grave Maclean declined to exhume: the reported $9 million lobbying contract linked to the Tinubu administration, designed to manage Nigeria’s image and counter damaging narratives in Washington. That is not the economy of screwdrivers. It is the economy of influence—polished, expensive, and professionally deceptive.

But that story is untidy. It implicates boardrooms. It dirties manicured Western hands. So it is easier to scrub one Nigerian man instead. Thus “Maclean” performs an unclean ritual: washing empire’s fingerprints off the weapon and wiping them onto the shirt of a screwdriver merchant.

None of this is to canonise Emeka Umeagbalasi. If his figures are inflated, his assumptions lazy, his verification weak, he deserves criticism. Advocacy dressed as statistics can inflame fear and distort policy.

But criticism is not scapegoating. Nigeria’s killing fields are real. Its kidnapping economy is real. Its church raids are real. Its mass graves do not vanish because a dataset is imperfect. When worshippers are driven into forests at gunpoint, they do not pause to ask whether their abduction meets the methodological standards of a New York newsroom.

If The New York Times wished to practice genuine investigative journalism, it would widen its lens: to Reverend Hayab in the North, to grieving villages in the Middle Belt, to Muslim communities equally ravaged, to the lobbying firms drafting talking points in Washington, to the politicians monetising faith, to the Nigerian state that cannot or will not count its dead. Those are the stories that demand investigation. Instead, readers were offered a small burial in Onitsha, officiated by a correspondent whose surname promises cleanliness but whose story leaves a moral stain.

In the end, Emeka Umeagbalasi may be a flawed activist. But he is not the architect of Nigeria’s bloodshed. And Reverend Joseph Hayab is not a screwdriver merchant. The real scandal is not that Nigerians speak imperfectly about their wounds, but that powerful newspapers listen selectively, ears wittingly tuned not to suffering, but to stories that flatter empire’s innocence. That is the unclean work. And no surname, however hygienic it sounds, can wash it away. Not even an OMO detergent, Hypo bleach, or Maclean toothpaste!