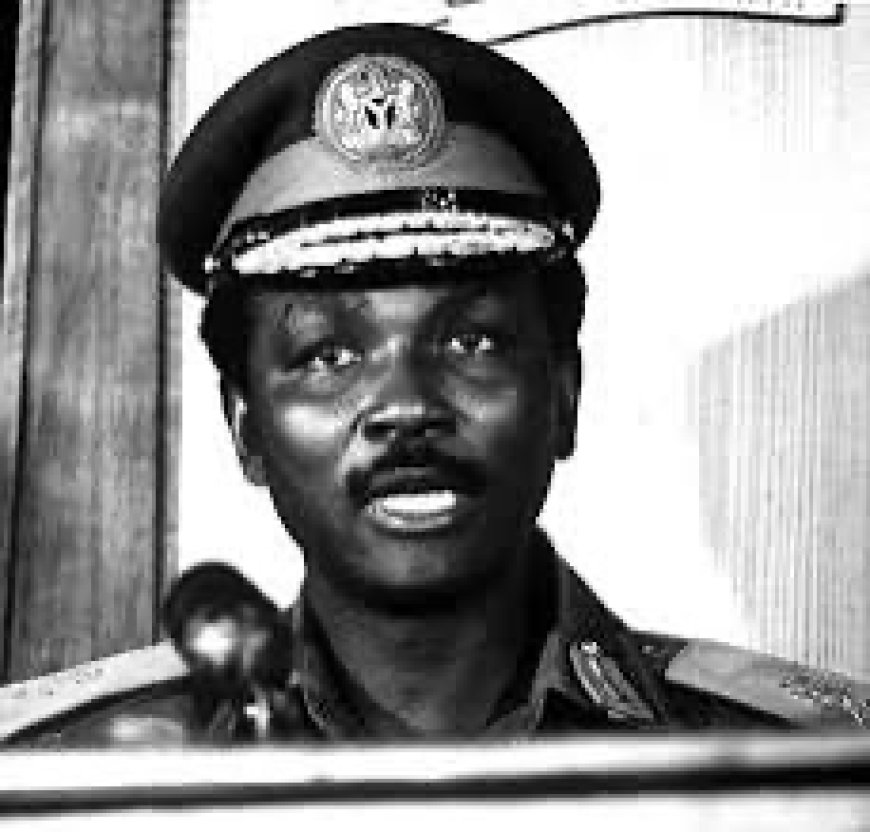

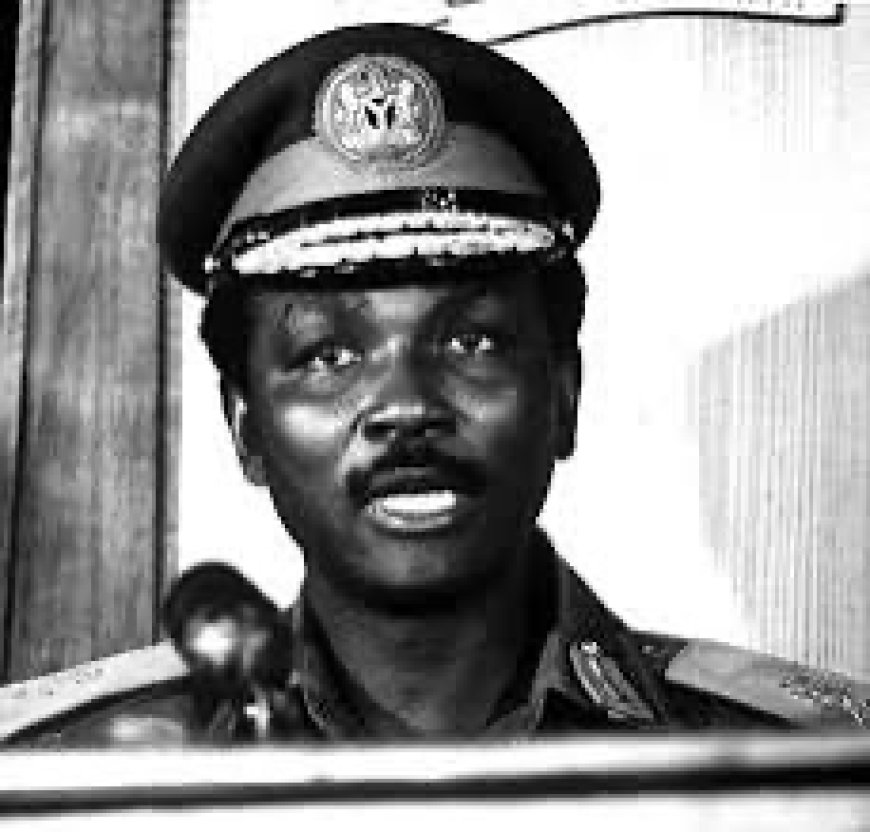

“I always remember the civil war,” said General Yakubu Gowon recently, with the air of a man remembering a stormy afternoon long ago. “It was the most difficult period of my life,” he added, evoking the image of a tormented philosopher reluctantly caught in history’s cruel tide.

He is a noble sufferer, indeed.

Gowon, Nigeria’s Head of State during the 1967–1970 Civil War, would like us to know that the war wasn’t really his idea. “It was not my choice,” he assures. He didn’t pick up the phone and call for Biafra to be starved into submission. The war, apparently, just happened, like rain or the common cold, and he, poor fellow, had no umbrella.

And what was this heroic general to do when his country began to split apart? “I had to be there and do what I did in order to keep this country together,” he said, invoking the sacred mantra of Nigerian nationalism: To keep Nigeria one is a task that must be done—even if that task required the systematic starvation of over two million people, mostly children. Even if it meant rejecting peace accords, shelling civilian targets, and blockading food and medicine. A small price to pay for the great and holy cause of unity.

And yet, he insists, without flinching: “It was never hatred against any people, I can assure you.” Never mind that the war strategy involved cutting off humanitarian aid. Never mind the unforgettable images of malnourished Biafran children with sunken eyes and bloated stomachs that haunted global conscience. Never mind the Red Cross being obstructed and missionaries pleading in vain. It wasn’t hatred. It was, one assumes, a paternal correction of misguided children. The bombs? A tough-love lullaby. The blockade? A stern moral lesson.

Let’s be fair. Gowon did not invent the hallowed national hypocrisy; he merely perfected its art. After all, this is a country where “No Victor, No Vanquished” was declared in one breath, while the vanquished were left to rebuild their scorched homes with silence, shame, and second-class status. A country where history is scrubbed clean by the victors, and war crimes are rebranded as patriotic service.

Still, Gowon’s image today is that of a gentle, grey-haired elder statesman. He prays. He fasts. He gives speeches. He attends church conferences and interdenominational love feasts. In a land where warlords become worship leaders, and repentance is optional so long as you’re polite about the past, he fits the part perfectly.

But let us not forget: history does not heal just because it is ignored. The wounds of Biafra still fester, disguised as “national issues”, ethnic mistrust, political exclusion, deliberate underdevelopment, and unhealed trauma. These things do not go away because a general remembers the war as “difficult.”

The real tragedy isn’t just the war itself; it’s the moral vacuum that followed. There were no truth commissions. No apologies. No restitution. No collective soul-searching. Only the silence of the grave and the denial of the pulpit. Nigeria, always eager to forgive without confession, simply moved on, dragging its buried history like a rattling chain.

Gowon wants us to remember the war, but only in the way he remembers it - as a noble burden, a sacred duty, a sorrowful necessity. But Nigerians, especially those whose families were decimated, displaced, or permanently altered, remember differently. They remember the screams, the hunger, the kwashiorkor, the ashes and debris of desolation, of deaths. They remember the hope that peace would come, only to be crushed by the steel boot of a government more interested in “keeping Nigeria one” than keeping Nigerians alive.

If there is a lesson to learn from Gowon’s remarks, it is this: memory without accountability is propaganda. Remembrance without remorse is revisionism. And unity without justice is not nationhood;it is occupation.

History has a long shadow, and it darkens the ground wherever denial walks. We owe it to the dead, not just to remember, but to remember truthfully.

So yes, General Gowon remembers. The question is: will Nigeria ever dare to remember fully?