When the Worm in ‘Dead Men Walking’ Turns

The English proverb, ‘Tread on a worm and it will turn,’ immortalized in John Heywood’s collection and echoed in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part III, is a timeless warning against the perils of underestimating even the weakest of adversaries.

By Chris Uchenna Agbedo, PhD

The English proverb, ‘Tread on a worm and it will turn,’ immortalized in John Heywood’s collection and echoed in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part III, is a timeless warning against the perils of underestimating even the weakest of adversaries. As Clifford puts it, “Who scapes the lurking serpent’s mortal sting? Not he who sets foot upon her back. The smallest worm will turn, being trodden on, and doves will peck in safeguard of their brood.” Clifford’s words in the Shakespearean Play, remind us that the smallest creature, when pushed to the brink, will fight back. This wisdom resonates deeply with the Igbo proverbs about nchị, the grass-cutter that revs up its biting instinct when reminded (E chetere nchị arụ, ọ taa); and the little boiling pot that extinguishes the fire when ignored, (E lilie nwa ite, ọ gbanyụọ ọkụ). The metaphorical imageries capture a universal truth about resilience in the face of provocation. Together, they serve as metaphors for the deadly resurgence of terror groups recently dismissed by General Edward Buba as “dead walking men.”

On the eve of 2025, General blllu made a bold declaration: “…I will from this platform tell you we have buried them (terrorist leaders) on the battlefield, because that is their fate in 2025. They are dead men walking. C’est fini.” The statement, delivered with unmistakable bravado, seemed to be a psychological strike against insurgent groups threatening Nigeria’s stability. In less than two weeks into the New Year, the nation has been rocked by a resurgence of terrorist and bandit attacks. From the ambush in Katsina State’s Baure village, leaving 21 dead, to the brazen assault on a military base in Borno State, it appears these so-called “walking dead men” are not only alive but also emboldened. The critical missteps underlying the rhetoric, the symbolic metaphors of the worm, grass cutter, and little pot, historical examples of similar misjudgments, and the lessons the Nigerian military must urgently learn form the thrust of analysis.

The Nigerian military has faced relentless insurgent violence since General Edwards’ statement. The audacious raids, including the daylight ambushes and attacks on military installations, suggest that insurgents are not deterred by the declaration. The grass-cutter, often dismissed for its docility, reacts aggressively when provoked. The same holds true for terror groups. They thrive on being underestimated, turning derision into fuel for renewed aggression. The attacks in Katsina, Zamfara, and Borno tend to underscore their capacity to adapt and strike where the state appears complacent. These metaphors underscore the need for strategic humility and preparedness when confronting a determined adversary.

History is replete with cautionary tales of leaders who, driven by arrogance or misjudgment, underestimated their adversaries, often with disastrous consequences. These examples offer valuable insights into the dangers of overconfidence and the importance of strategic foresight. From the Battle of Teutoburg Forest to the attack on Pearl Harbor, these missteps remind us that hubris in warfare can provoke unexpected and devastating pushback. The Persian Wars (499–449 BCE), fought between the expansive Persian Empire and the independent Greek city-states, provide a timeless lesson on the dangers of underestimating one’s adversary. The Roman Empire, underestimating the resolve and strategy of Germanic tribes, suffered a humiliating defeat when three legions, led by General Varus, were ambushed and annihilated in the dense forests of Germania. Napoleon Bonaparte’s confidence in the Grand Armée’s strength led to one of the most disastrous military campaigns in history.

During the War of 1812, British forces underestimated American resolve and tactical preparedness. Despite superior numbers, the British suffered a crushing defeat at New Orleans, largely because of poor intelligence and overconfidence. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor is a case of the U.S. misjudging Japan’s willingness to strike preemptively. The attack devastated the U.S. Pacific Fleet, forcing America into World War II with a resolve that Japan had not anticipated. The insurgents’ counter-attacks since the start of 2025 resemble a calculated response to provoke the Nigerian military. The unintended consequence of Edwards’ rhetoric may be a rallying cry for insurgents, similar to how Pearl Harbor steeled American resolve. A prolonged counter-push by insurgents risks depleting Nigeria’s military resources and morale.

Lessons for counter-terrorism strategy, which underscore the imperative of strategic humility, entail avoiding provocative rhetoric, respecting the enemy’s capability, avoiding hubris, prioritizing intelligence, engaging strategic communication, adapting to dynamic threats, and most importantly, learning from setbacks. Each historical example highlights the importance of learning from miscalculations, which explains why the Nigerian military must reassess its approach and adapt. The Persian Wars, Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, and even the tragedy of Pearl Harbor illustrate the dangers of underestimating an adversary. As the Greek victory over the Persians demonstrates, underestimating an enemy is a cardinal sin in strategy.

Whether in war or diplomacy, arrogance blinds decision-makers to the complexities of their adversaries and the strength of their resolve. The Persian kings, despite their vast resources and ambitions, failed because they dismissed the capabilities of their opponents. The narrative of the Persian Wars underscores the wisdom of humility in confrontation. In every conflict, it is the leader who appreciates the perils of marching on the worm, the hunter who outthinks the grass cutter, and the strategist who respects the boiling pot that emerges victorious. In war, as in life, respect for the opponent is not a weakness; it is the foundation of a sound strategy. Both Darius and Xerxes failed to understand a fundamental rule of conflict: dismissive rhetoric can fuel an adversary’s resolve. The proverb – E lelia nwa ite, ọ gbanyụọ ọkụ (A little boiling pot, when disregarded, can extinguish the fire) – captures this perfectly. By belittling the Greeks, the Persian kings overlooked their potential, much like dismissive declarations today risk underestimating the ingenuity and resilience of terrorist groups. The grass cutter analogy, where provocation leads to harder biting, is also apt. Rather than cowing under pressure, insurgents have responded to the Nigerian military’s rhetoric with renewed aggression, proving that verbal posturing without corresponding action only invites more ferocity.

Rhetoric in warfare is as old as war itself, often used to bolster morale and intimidate adversaries. However, it becomes a double-edged sword when it belittles an opponent’s capability, provoking them to prove their strength. Victory in counter-terrorism requires less bravado and more strategic foresight – actions that speak louder than words. The grass cutter (Thryonomys swinderianus), apart from its highly-valued nutritional value, is also known for its resilience, adaptability, and defensive aggression when cornered. These mammalian traits mirror the dynamics of insurgents and bandits in Nigeria – groups that, like the grass cutter, are deceptively formidable when provoked.

Understanding the instinctive biting trait of the grass cutter and its other notable characteristics – adaptability, defensive aggression, and resourcefulness – predisposes the Nigerian military to assume the hunter’s responsibility of outthinking the game, the grass cutter. Grass cutters thrive in diverse environments, from grasslands to farmlands. Similarly, insurgents and bandits are adept at adapting to changing terrains – moving from forests to urban areas or operating from hideouts undetected. When threatened, the grass cutter employs its sharp teeth as weapons of defence. In the same way, insurgents, when cornered or provoked, retaliate with heightened ferocity, as seen in recent attacks on military formations and communities. Grass cutters are nocturnal and resourceful, often foraging at night to avoid predators. Likewise, insurgents operate under the cover of night or exploit weak points in security architecture to launch attacks.

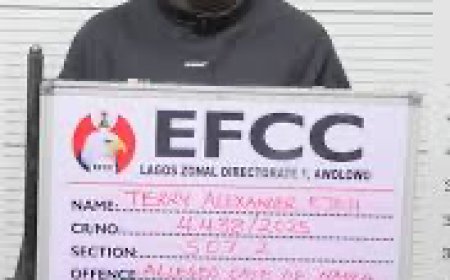

While the grass cutter’s bite is instinctive, the hunter’s success lies in strategy, patience, and preparation. The recent wave of attacks following the “walking dead men” rhetoric highlights the pitfalls of underestimating adversaries and relying on intimidation rather than strategic planning. To outmanoeuvre insurgents, the military must prioritize intelligence gathering and predictive analytics. Similarly, counterinsurgency efforts must focus on surgical strikes that neutralize key threats without collateral damage, which could alienate local populations. For instance, a Zamfara lawmaker, Maharazu S. G. Faru regretted that the NAF’s airstrike on the Tungar Kara community on Saturday 11 January 2025, mistakenly hit members of the Zamfara Community Protection Guard (ZCPG), local vigilantes and residents, leaving at least 16 people dead. However, NAF spokesperson AVM Akinboyewa in a statement emphasised that no credible evidence supports reports of civilian casualties during its airstrikes on terrorist hideouts, including areas linked to notorious bandit leader Bello Turji. For a moment, the true situation appeared befogged by a blitz of claims and counter-claims. Later, a NAF Fact-Finding Team led by Air Voice Marshall Edward Gabkwet to the affected Tungar Kàrà community admitted impact of mistaken airstrikes. That admission of mistake on the part of NAF underscored transparency, accountability, and sincerity of purpose that deserves commendation.It goes to underscore the complexity of asymmetrical warfare and the fluidity of counter-terrorism operations, which the Nigerian Military is struggling tenaciously to get a better handle of the situation.

All the same, the annals of history and Igbo wisdom converge on a central truth: no adversary is too small or too diminished to ignore. The worm, when stepped on, turns; the grass cutter, when provoked, bites even harder; the little pot, when overlooked, extinguishes the fire. General Edwards’ ‘dead walking men’ declaration, while perhaps well-intentioned, must be tempered with humility and strategic foresight. To secure victory, the Nigerian military must channel its energy into outthinking and outmaneouvring its adversaries rather than provoking them into proving their strength. Otherwise, when the worm in dead walking men turns, the outcome would predictably be nothing but catastrophic! Kudos to the Nigerian Military for the successes so far recorded. Aluta Continua! For the unfortunate Nigerian citizens ‘caught in the middle’ of the counter-insurgency operations, may their souls find eternal rest in the Lord’s bosom, Amen.

.

AGBEDO, a Professor of Sociolinguistics, University of Nigeria, Nsukka & Public Affairs Analyst, writes from Nsukka

What's Your Reaction?