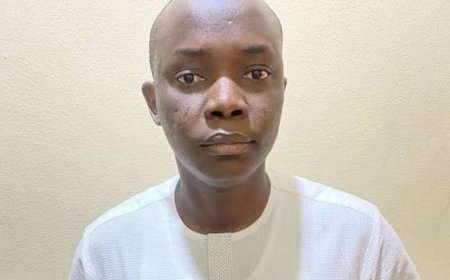

Once again, Fabian Ezema, the internationally- renowned solar power and nanoscience professor, has thrust the University of Nigeria Nsukka into global spotlight. Prof Ezema is on the list of

the recently released Stanford Top 2% Scientist List for 2025 , one that should inspire both pride and sober reflection.

More than 230 Nigerian researchers have earned a place on this highly competitive roll call of global academic excellence, spanning medicine, engineering, environmental science, economics, and several other disciplines. Their recognition affirms that world-class research is not the sole preserve of foreign institutions but is being nurtured, against all odds, on Nigerian soil.

On the surface, this should be an unalloyed moment of celebration. In a global narrative that too often casts Nigeria as a place of unfulfilled promise, corruption, industrial actions, banditry, and infrastructural decay, the emergence of over 230 scholars among the world’s most influential scientists disrupts the stereotypes. It signals that despite systemic neglect, Nigerian intellectual firepower continues to blaze. However, beneath the applause lies a more complex story, one that forces us to reckon with uncomfortable truths about the state of higher education, research, and innovation in Nigeria.

In a recent government-owned television news report, one of the recipients of the award publicly thanked the current administration for providing an enabling environment for research. It was a gesture perhaps intended to sound patriotic or diplomatic, but it struck a discordant note with those who know the harsh realities of Nigerian scholarship. Prof. Ezema, responding on a common WhatsApp platform, where colleagues congratulated him, cut through the veneer of official self-congratulation with a blunt rejoinder. His words deserve to be recorded in full, for they expose the paradox at the heart of Nigerian academia:

“Appreciation to President not necessary. If I had the opportunity, I would have told the President all the facilities I have in my lab that brought me among the 2% came from outside Nigeria. The XRD machine is from a grant through UK government, now it is down; we cannot repair it.

"The electrochemistry and specialized spin coating equipment are partly from US Army and UK government. The lab enabled 24 hours light PV powered came from German government, but not for intensive research. The US Army grant bought us FTIR and Photoluminescence spectroscopy, which are now dead and need support.

"The ball milling facilities got through the UK government grant is also grounded. The lab is littered with broken facilities, which the local grants could not build up. The country is not part of the making of my own 2% ranked world scientists except paying monthly less than 400 USD salaries. In fact I use part of the salary to support the lab and prevent it from collapsing. Praising government for what they didn’t contribute in making is part of our problem. Please, give me thumbs up; I made the top 2% world scientists. Praise God.”

There, in his unembellished voice, lies the truth. Nigerian scholars thrive not because of the system, but in spite of it. And herein too lies the paradox of brilliance amidst decay.

Ezema’s testimony is not unique but symptomatic of the struggles faced by countless Nigerian researchers. Laboratories across the country are underfunded, libraries are outdated, and frequent power outages cripple experiments. When specialized equipment—like the XRD machine in Ezema’s lab—breaks down, there is no domestic ecosystem of technical support or maintenance. In many cases, scientists either abandon their projects or turn to foreign partners for help. This reality makes Nigeria’s presence on the Stanford list paradoxical. It is not a story of a supportive state cultivating excellence; it is a story of individuals producing brilliance while carrying the heavy burden of systemic neglect. What ought to be a national triumph risks becoming a hollow victory if the country does not confront its failure to nurture, retain, and reward intellectual talent.

Consider the broader picture. The federal allocation to education in Nigeria remains far below the UNESCO benchmark of 15–20% of the national budget, hovering in single digits year after year. The Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) has spent more time in strikes than in classrooms in the last two decades, largely due to unpaid salaries, decayed infrastructure, and lack of research funding. In fact, at the point of writing this piece, the lecturers’ union had in a Notice of Strike Action released and dated 28th September 2025, given a 14-day ultimatum to the Federal Government within which to address clearly outlined seven-point demand. “If at the end of the fourteen days ultimatum, the Federal Government fails to address these issues,” according to the Statement, “the Union may have no option than to, first, embark on a two-week warning strike and thereafter, a total and indefinite strike…”

Oh God! Who did this to us?

A number of national dailies carried it as a headliner in differing degrees of grimness – all depicting the inevitability of total darkness threatening to eclipse Nigeria’s university institutions, where the likes of Prof Fabian Ezema and his 230 co-miracle workers are breaking new grounds in scientific and technological innovations against all odds. Apart from chronic industrial actions, young scientists migrate in droves, part of the so-called Japa wave, seeking the opportunities their homeland denies them. Yet, even within this stifling and suffocating ecosystem, 230 scholars managed to rise to global prominence. If this does not underscore the resilience and perseverance of Nigerian intellectuals, what else does?

And talking about the politics of empty praise, the irony of the Stanford recognition lies in how quickly it is co-opted into political propaganda. It is easy for governments to bask in the reflected glory of these achievements, using them as evidence of their “support” for education. But as Prof. Ezema rightly argues, praising government for what it has not contributed to is part of Nigeria’s problem. Empty flattery feeds complacency. It absolves leaders of accountability. It transforms genuine intellectual feats into tokens for official rhetoric. If Nigeria is to move forward, the narrative must shift. Scholars must be honest, as Ezema was, in telling the world where the real support comes from: foreign donors, international collaborations, and their own personal sacrifices. Citizens must resist the temptation to dress up global recognition as proof of domestic progress. And policymakers must face the hard truth that Nigeria is harvesting the fruits of trees it never watered.

What then is the cost of systemic neglect? The neglect of research is not just a matter of prestige; it has tangible costs. Nations that dominate the future are those that convert knowledge into innovation - vaccines, renewable energy technologies, artificial intelligence applications, sustainable agriculture systems. Nigeria has the intellectual firepower to lead in these areas, but without infrastructure, funding, and policy alignment, the potential is squandered.

Take energy, for example. Nigerian scientists like Ezema, whose lab runs on photovoltaic power supported by the German government, are experimenting with renewable solutions. But how much of that knowledge is being scaled up nationally to reduce the country’s crippling dependence on fossil fuels and unreliable grids? In medicine, Nigerian researchers contribute to global studies on infectious diseases, but local hospitals remain ill-equipped.

The tragic fate of Sommie Maduagwu, the rising star of Arise News Channel is one of the latest testimonies of how the Nigerian healthcare delivery system can 'happen' to her citizens. Ironically, Sommie had in one of her most recent tweets, prayed against the fate that eventually plucked the flowers of her prime! In agriculture, breakthroughs that could revolutionize food security exist in theory but are rarely translated into practice. The result is a sickening cycle of intellectual export. Nigerian scholars produce knowledge that benefits other countries more than their own. The brains remain Nigerian; yet, the benefits are outsourced and harvested abroad.

The foregoing makes a call for an institutionalised knowledge economy in Nigeria justified. The Stanford list should therefore be more than a moment of applause; it should be a clarion call. Nigeria must finally decide whether it wants to build a knowledge economy. This requires more than token gestures and pittance as remuneration system. It demands adequate funding for research and higher education, not the crumbs currently allocated, but sustained investments that meet international standards; infrastructure renewal, modern laboratories, libraries, and reliable energy systems to provide a foundation for innovation; accountable governance, ending the culture of self-congratulation and redirecting praise toward the actual doers of research; partnerships with industry, i.e., ensuring that research findings translate into products, services, and technologies that solve national problems; retention strategies, providing incentives, grants, and recognition to keep Nigerian scientists at home, rather than fueling the brain drain.

Can Nigeria learn from the world? Other countries have faced similar challenges and turned them into opportunities. India, once mocked for its “brain drain,” has built research hubs that now attract returnees from Silicon Valley. Rwanda, scarred by genocide, is investing in technology and research parks as engines of national recovery. South Korea rose from poverty to prosperity not by extracting resources but by investing heavily in education and science. Nigeria, with its population of over 200 million and vast talent pool, can do the same—if it finds the ever-elusive political will.

In conclusion, the Stanford Top 2% Scientist List is both a moment of pride and call for responsibility for Nigeria. Scholars like Prof Fabian Ezema, by sheer tenacity, dint of hard work, and galvanic purposefulness, have carved out spaces of excellence in a desert of abject neglect. Their recognition affirms what is possible when the stubborn flame of intellectualism refuses to be extinguished. But it also exposes the down side of a country that seeks to celebrate what it did not toil and sweat to cultivate. Whether this becomes a turning point depends on Nigeria itself. Will the nation continue to celebrate brilliance while starving it of support? Or will it use this recognition as a catalyst to build a genuine knowledge economy?

Prof. Ezema’s unvarnished words should serve as both subtle rebuke and roadmap: “Praising government for what they didn’t contribute in making is part of our problem. Please give me thumbs up, I made the top 2% world scientists. Praise God.”

Nigeria must learn to give the right thumbs up, not to a system that takes credit for what it did not build, but to the great scientists, who daily keep the flame of excellence alive in spite of everything.

Only then will the Stanford Top 2% Scientist List not just be a fleeting headline but the beginning of a national rebirth for the Nigerian State @65 today.

For now, kindly join me in congratulating this eminent scholar, the intellectual colossus (Mgbedike) of our time, Prof Fabian Ezema, Fellow, Nigerian Academy of Science, African Academy of Science, and Director of Research, Development, and Innovation, University of Nigeria!

To God be the glory.