Political Musing of Thursday October 30, 2025

By Ike Abonyi

“ _We must make our choice. We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we cannot have both.” —_ Louis D. Brandeis

In 2018, during the administration of the late President Muhammadu Buhari, the Deputy Senate President of the 8th National Assembly, Senator Ike Ekweremadu, posed a provocative hypothetical question on the Senate floor: “Who says the Army cannot take over?” While this question was alarming, the circumstances that prompted it were concerning. Seven years later, the situation has not improved enough to render such inquiries unnecessary.

The ongoing discussions about military coups in Nigeria, despite 26 years of uninterrupted civilian rule, reveal significant issues within our democratic framework. While we identify as a democratic nation, the failure to conduct free, fair, and credible elections—a fundamental aspect of democracy—raises serious questions about the health of our political system. Our democracy remains compromised as long as we allow anti-democratic elements, impunity, corruption, tribal and religious bigotry to prevail.

Consequently, the frustrations often expressed by citizens regarding the idea of a coup should not be dismissed outright. Leaders may quickly label such sentiments as misguided or sacrilegious without addressing the underlying concerns driving these discussions. When people feel trapped and see no improvement in their circumstances under the current governance, it is only natural for them to voice their discontent.

Senator Ekweremadu's outburst came just three years into the All Progressives Congress (APC) administration, which had initially been celebrated for defeating an incumbent in a free, fair, and credible election—one that elevated Nigeria’s democratic profile in the eyes of the international community. Unfortunately, we currently find ourselves amidst a resurgence of coup-related rumours, particularly since Bola Tinubu assumed power and introduced draconian reform policies, echoing Senator Ekweremadu’s inflammatory remarks.

Ekweremadu's question did not arise from nowhere; it stemmed from his personal experiences of feeling threatened by the rampant political thuggery across the country. He was specifically responding to a report from a senator in Kogi State regarding his young and controversial governor, Yahaya Bello, who was allegedly sending political thugs to threaten him and force him out of his constituency. As senator after senator condemned the governor’s apparent intolerance of opposing views, recalling similar incidents involving the outspoken Senator Dino Melaye, Ekweremadu summarised the situation by stating, “The problem in Nigeria is that our democracy is receding. The house of a senator was destroyed in Kaduna State. We are talking about a former senator and former Minister of Defence, Rabiu Kwankwaso, who was prevented from going to his state, where he served as governor for eight years. In Kaduna, Senator Shehu Sani cannot organise a meeting in his constituency, and we are talking about a democracy?”

Many senators echoed his concerns, highlighting the troubling climate of political intolerance that undermines our democracy. Instances of violence against political figures, such as the assault on a Catholic archbishop in Imo State allegedly orchestrated by the then-governor, all serve as stark reminders of the challenges our democracy faced at that time. Senator Ekweremadu’s intention was clear: to emphasise the threats to democratic governance and the need for vigilance. Unfortunately, some media outlets misinterpreted his statement as a call for a coup, for military intervention, but what he actually aimed to underscore was the urgent necessity to safeguard our democratic principles.

The military has sought to clarify its position by reassuring the public of its commitment to remaining apolitical. Senator Ekweremadu's extensive experience in parliamentary governance informs his comments, which are not naive but rather reflect a deep concern for the state of our democracy.

In 2021, the discussion surrounding potential military coups in Nigeria resurfaced when Chief Robert Clarke, a Senior Advocate of Nigeria and ally of the then-regime, suggested military intervention as a corrective measure if politicians failed to adapt. This statement, made during a prominent political program on Channels Television, raised questions about the necessity of such drastic measures, especially given Clarke's close ties to Alhaji Abubakar Malami, the then Minister of Justice and Attorney General.

The swift response from military authorities and the Department of State Security (DSS) then sparked further public interest and concern. This situation prompted debates, particularly in light of recent leadership changes then among service chiefs, who had overstayed their tenure and were viewed as part of the systemic issues within the military and security sector.

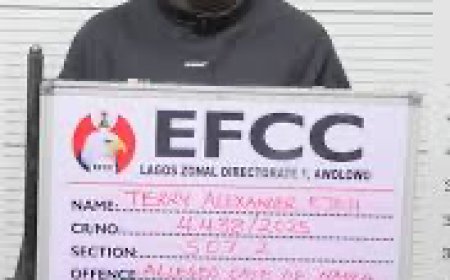

The point being underscored here is that rumours of coups are not new since the APC government came to power in 2015; they reflect deep-seated concerns among Nigerians regarding democracy and governance. Despite the most recent official denials from the Defence Headquarters (DHQ) about any alleged coup plots lately, these rumours gained traction following a weak justification for the arrest of some military officers thought to be hatching a coup. The unexpected dismissal of all service chiefs, including the Chief of Defence Staff, heightened speculation, as the belief persists that every smoke has fire underneath. The timing of this top officers' reshuffle raises questions about its connection to the coup rumours, particularly amid ongoing challenges such as economic hardship, alleged stalled promotions within the military, and a culture of nepotism and corruption in the system.

Many Nigerians are facing significant challenges, including poverty and insecurity, which have led to growing discontent with the government's ability to address these urgent issues. Within the military, there are legitimate grievances, such as stagnant career advancement and inadequate welfare, capable of creating a potentially volatile environment.

Additionally, the military, as an integral part of society, is not immune to widespread issues of corruption and perceived impunity that can erode public trust in institutions. The historical context of military coups in Nigeria, beginning with the first coup in 1966 and continuing through the one in 1983, highlights a persistent pattern of instability.

The current political landscape, marked by the ruling APC and President Bola Tinubu's regime showing signs of suppressing opposition voices, is genuinely raising concerns about the health of Nigeria's democracy. A robust democracy relies on a vibrant opposition; thus, when opposition parties are marginalised and threatened, the core principles of democracy are at risk. Today, key opposition parties, including the main opposition Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), Labour Party, Social Democratic Party (SDP), New Nigeria Peoples Party, NNPP, and the newly formed Coalition, the African Democratic Congress (ADC), are all experiencing crises rooted in the actions of the ruling APC and President Tinubu’s spin doctors. This situation appears aimed at denying strong candidates a platform to seek the people's votes. Exacerbating this issue is the apparent assimilation of the legislature and the judiciary arm of government into the executive branch, thereby undermining checks and balances, which are critical to democratic governance.

To strengthen democracy in Nigeria and mitigate concerns about the possibility of a coup, it is essential for the government to actively address the public's concerns. When citizens feel excluded from their government, the threat of revolutionary measures, including military intervention, becomes more pronounced.

Ultimately, the resilience of Nigeria's democratic framework depends on the government's ability to respond to the needs of its citizens. Ensuring quality leadership, transparency, accountability, and institutional stability is vital if military rule is to remain an unthinkable option. By fostering an inclusive and responsive governance system, Nigeria can strive for a brighter and more stable democratic future. In the absence of these essential elements, the prospect of military intervention may continue to dominate public discourse.

In summary, democracy is a government of the people, by the people, and for the people, meaning that the citizens are the cornerstone of a viable democracy.

A position strongly reinforced by an American novelist and longtime Senate reporter, Allen Drury, when he stated copiously what Nigerians need to know, that "Democracy is the most fragile thing on earth, for what does it rest upon? You and me, and the fact that we agree to maintain it. The moment either of us says we will not, that’s the end of it. It doesn’t rest on anything but us; it doesn’t rest on armed force; the moment it does, it isn’t democracy. It isn’t something to kick around or experiment with.” God help us.