Naming the Season: Christmas, Metaphor, and the Limits of Licence

The condemnation by the Christian Association of Nigeria, CAN, of the movie title A Very Dirty Christmas has once again thrust Nigeria into a familiar but unresolved tension point: the uneasy intersection of faith, art, regulation, and public sensitivity.

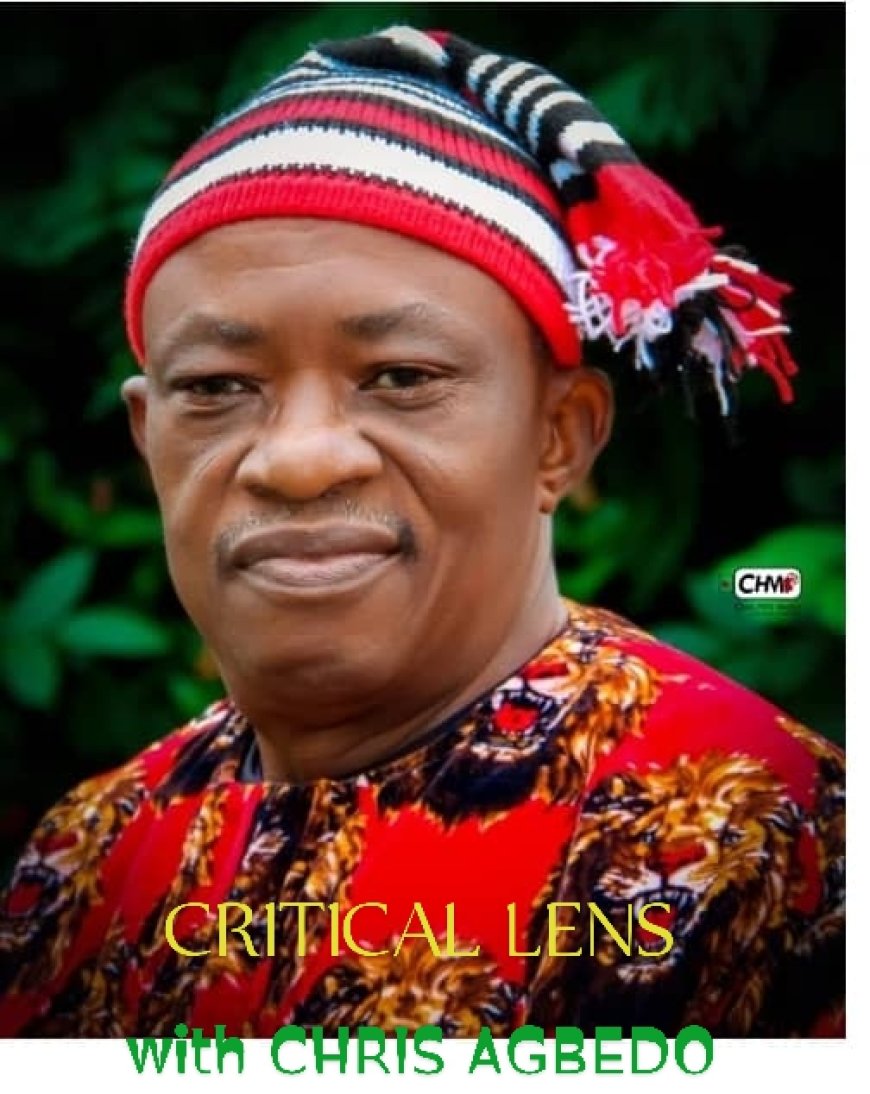

By Prof Chris Agbedo

The condemnation by the Christian Association of Nigeria, CAN, of the movie title A Very Dirty Christmas has once again thrust Nigeria into a familiar but unresolved tension point: the uneasy intersection of faith, art, regulation, and public sensitivity. What might otherwise have been a fleeting entertainment headline has morphed into a national conversation about reverence, freedom of expression, cultural context, and institutional responsibility.

CAN’s position, articulated by its President, Archbishop Daniel Okoh, is neither ambiguous nor mild. The Association considers the title offensive to the Christian faith, arguing that it trivialises the spiritual essence of Christmas, a season that, for Christians, commemorates the birth of Jesus Christ and symbolises purity, peace, love, and redemption. By pairing the sacred with the adjective “dirty,” CAN contends, the title reduces a solemn religious observance to something crude and sensational, thereby diminishing its spiritual significance.

On the surface, CAN’s objection appears straightforward: a defence of religious dignity in a plural but deeply religious society. Yet beneath the surface lies a more complex set of questions that Nigeria has often postponed rather than answered – questions about artistic licence, semantic interpretation, regulatory vigilance, and the limits of cultural sensitivity in a diverse democracy.

To begin with, it is important to acknowledge that CAN’s reaction is not occurring in a vacuum. Nigeria remains a society in which religion – Christianity, Islam, and traditional beliefs – plays an outsized role in public life. Sacred seasons are not merely private spiritual moments; they are communal markers embedded in social rhythms, public holidays, and collective memory. Christmas, in particular, carries immense emotional and symbolic weight for millions of Nigerians. In such a context, sensitivity to religious language is not an unreasonable expectation.

From this standpoint, CAN’s discomfort with the word “dirty” is understandable. Language matters, especially when it touches sacred symbols. Words carry connotations beyond dictionary meanings, shaped by culture, history, and emotion. For many believers, the juxtaposition of “Christmas” with “dirty” instinctively feels irreverent, regardless of the filmmaker’s intent or the narrative content of the movie itself. In a society already strained by moral anxieties and social fractures, as Archbishop Okoh noted, perceived trivialisation of sacred values can easily deepen mistrust and resentment.

However, understanding is not the same as uncritical endorsement. A cerebral engagement with the issue must also consider the other side of the equation, that is, the nature of artistic expression and the elasticity of language in storytelling. Film titles, particularly in contemporary popular culture, are often metaphorical, ironic, or deliberately provocative. The adjective “dirty” does not always denote moral filth or sacrilege; it can signify chaos, complication, irony, or even humour within a narrative arc. Without engaging the content of the film itself, there is a risk of collapsing metaphor into malice.

This raises a crucial question. Should offence be determined solely by perception, or must intent and context also matter? If every artistic expression that unsettles a faith community is automatically deemed unacceptable, creative space shrinks, and public discourse becomes hostage to the most easily offended sensibility. Democracies thrive not by eliminating discomfort but by managing it through dialogue, proportionality, and mutual respect.

CAN’s editorial intervention goes further by interrogating regulatory oversight. The Association has demanded explanations from the National Film and Video Censors Board, NFVCB, on how such a title passed through official scrutiny, particularly during the Christmas season. This aspect of the controversy deserves serious attention. Regulatory bodies exist precisely to mediate between creative freedom and public interest. If the NFVCB approved the title, it implies either that existing guidelines are inadequate, inconsistently applied, or interpreted in ways that no longer align with prevailing social sensitivities.

Yet, regulation must be careful not to slide into cultural paternalism. A censor’s role is not to enforce theological orthodoxy but to ensure that content does not incite violence, hatred, or gross indecency. The question, then, is whether a provocative title, absent explicit blasphemy or incitement, meets the threshold for regulatory intervention. If regulatory standards are to be recalibrated, that process must be transparent, inclusive, and principled, not reactive or driven by episodic outrage.

The naming of Ini Edo by CAN introduce a crucial aspect of the discursive tangle. As a prominent Nollywood figure, her visibility makes her an easy symbol of the industry itself. CAN’s call for her to apologise and show sensitivity reflects a broader expectation that cultural influencers bear special responsibility in shaping public morals. While this expectation is not entirely misplaced, it also risks personalising what is fundamentally a structural issue involving creative choices, industry norms, and regulatory frameworks.

Nollywood, for its part, operates in a cultural ecosystem where religious themes are frequently explored, sometimes reverently, sometimes critically, and sometimes commercially. The industry has produced countless films that dramatise spiritual warfare, miracles, and moral redemption—often to the applause of faith communities. It is therefore neither uniformly hostile nor indifferent to religion. What is required is not blanket condemnation but clearer internal conversations within the industry about how sacred symbols are framed, marketed, and contextualised.

One commendable aspect of CAN’s response is its stated commitment to peaceful engagement. The Association has not called for bans, protests, or punitive sanctions, but for reconsideration, apology, and dialogue. This posture matters. Nigeria has seen too many instances where perceived religious offence escalated into censorship hysteria or even violence. By choosing institutional engagement over street outrage, CAN has set a tone that should be reciprocated with seriousness rather than defensiveness.

Ultimately, this controversy reveals less about a single movie title and more about Nigeria’s unresolved negotiation between faith and freedom. A mature society must be capable of holding two truths at once: that religious communities deserve respect, and that artistic expression requires room to explore, question, and even unsettle. Respect does not mean immunity from metaphor, just as creativity does not mean exemption from responsibility.

The constructive path forward lies in dialogue, not decrees. Filmmakers should be more attuned to the symbolic weight of religious language in a deeply devout society. Regulators should clarify and consistently apply standards that balance sensitivity with freedom. Faith bodies should engage art not only as something to be protected from, but as a space for conversation about values, ethics, and social realities.

If this episode leads to deeper reflection rather than hardened positions, it may yet serve a redemptive purpose. In that sense, the real test is not whether ‘A Very D**ty Christmas’ keeps or changes its title, but whether Nigeria can learn to negotiate its differences with calm eyes, measured words, and a shared commitment to mutual respect.

Agbedo, Ph.D, a Professor of Linguistics University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Fellow, Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study, Amsterdam, is a public affairs analyst.

What's Your Reaction?